"If recent pop culture history is any indicator, the debate over global warming may be settled (if it gets settled at all) not so much by science as by art and mythmaking.

Discussions on climate change are at an impasse. Some of those who fret about man-made emissions of greenhouse gases claim it's a threat that trumps all others, including terrorism. Others argue that we have more pressing concerns, such as the developing world's dehumanizing poverty and disease. They posit that even if global warming is a problem, proposed cures, such as the Kyoto Protocol, would hamstring the global economy and be more harmful.

[...]

It may seem odd that the ultimate in nerdy science policy issues has morphed into a sexy canvas for sociopolitical commentary. But maybe there's an important lesson here.

At some level, science probably will never resolve what to do about global warming. Climate change is complex, with scores of variables and time-frame considerations of decades and even centuries. Both sides have substantial data that support their points of view. Both sides also believe that to the extent the science is "settled," it's settled in ways that undergird their respective policy prescriptions.

But science is inherently descriptive, not prescriptive. It can only inform us about the likely consequences of actions. It doesn't tell us - and shouldn't tell us - if those actions should be taken. That arena is reserved for politics, where moral judgments and philosophical views matter alongside scientific truth. Morality and philosophy are often best examined and illustrated not through scientific discourse but through narratives, theology and storytelling.

[...]

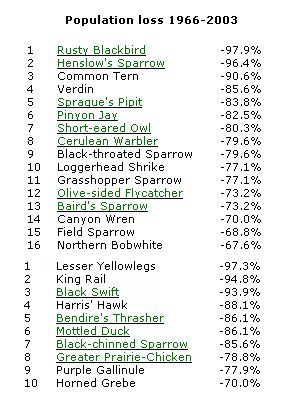

Crichton, who considers environmentalism to be a kind of religion, was motivated to write his story in response to an earlier bit of eco-mythmaking, one that had real-world consequences. Rachel Carson's 1962 book "Silent Spring" - a kind of artistic precursor to "The Day After Tomorrow" in that it speculated about a future in which songbirds had been killed by industrial chemicals and spring was thus silent - is one of the sacred texts of the green movement. It helped galvanize a global ban on DDT, a chemical used against malarial mosquitoes. Over time, several of Carson's claims about DDT have been debunked, but the ban yielded millions of malarial deaths in the developing world.

Crichton sees parallels to this and other environmental crusades in the concerns over global warming today.

Crichton sees parallels to this and other environmental crusades in the concerns over global warming today.

Much of the rancor over global warming reflects a clash of conflicting moral visions of mankind and the future. As such, we can expect artistic - as well as scientific - debate over it to flourish."

Nick Schulz/LATimes 15.Dec.04

The trivial part of Schulz' smarmy Judeo-Christian commercial message is its obvious attempt to reduce the information, and the resistance to the information, to a pop-culture disagreement, the insinuation of a different template entirely, where Schultz' agenda has equal standing with "environmentalists'". It's a consumer choice, the way religion is a consumer choice now, based a little on your family and a little on your community, and a little on what you're looking for as a consumer of religion. It doesn't matter which denomination you pick as long as it's not Islam, or one of the eastern superstitions, or God forbid, a pagan nature-cult.

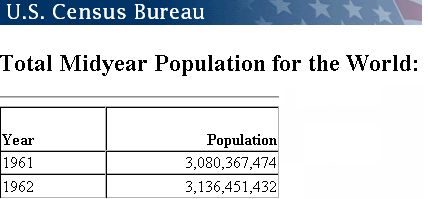

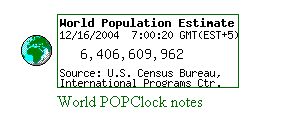

The less trivial but still not central part is Schultz' nonsensical assertionless-asserting that Carson's predictions were hysterical, and that because of them millions of people have died. As the graphs show, even though millions of people died from malaria, the world population still doubled in the 42 years since Rachel Carson's book was published.

You'd be on safe ground wagering Shultz hasn't heard too many songbirds lately. And it would be exciting to listen to him explain away the deaths of Iraqi and Palestinian and Indonesian and Malaysian and Afghani women and children as being far less important than the deaths of malaria victims.

Millions of people have also died in auto accidents in the last forty years, around 2 million in the US alone, the result of a bizarre form of transportation that involves, for most people, moving a ton of steel, daily, back and forth to work. Auto emissions being a primary cause of acute climate change as well, though Schultz doesn't seem to be concerned with that. Nor, I imagine would it bother him much to know that the single largest cause of death for children in the United States is the automobile.

The central part is why. It's easy to see it as cumulative inertia, things are this way, and the people who are most comfortable, whose lives are dependent on the way things are, will resist profound change. The way an addict will squirm and twist away from the obvious damage and inevitable destruction his habit brings, and the suppliers will rationalize their part in that destruction as a business opportunity.

But as Gary Webb showed us years ago, there may be more to the pattern of addiction than character flaws and community failure; and as his death showed us this week, there are still spooks and shadows at work in our lives. I don't think Schulz knows the men who killed Gary Webb, or David Kelly, or even Jason Korsower - he's a lightweight pseudo-journalist, not an intelligence agent - but he works for the same people they work for.